The word “ballot” comes from the Italian word pallotte, meaning “little ball”. In 16th century Venice, electors would drop a white ball into an urn if they agreed with some proposal and a black one if they did not (hence the term “blackballing”). As the years went by, its meaning then grew to include tickets and paper too. Nevertheless, the study of elections remains the study of balls and urns.

As political scientists, we share our obsession with balls and urns with those who study probability. Often, the real world is messy and the details we consider important are actually distractions. So probability theorists simplify their problems as much as possible, often leading them to think of the world in terms of balls and urns.

In this post, I will marry these two perspectives by using a problem from combinatorics to solve a problem in politics. In particular, I’m going to elaborate a revised version of the logical model that Shugart and Taagepera (2017) propose for the number of seat winning parties,

A Logical Model of District Level Seat Winners

Before I build my model, it’s worth discussing “quantitatively predictive logical models” (Taagepera 2008) and how Shugart and Taagepera (2017) derive their model of the number of seat winning parties at the district level.

The basic premise behind logical models is to think before we fit. In other words, to avoid what McElreath (2020) calls “generalised linear madness”: blithely fitting linear models to data without first thinking scientifically about how our data might be generated. The general process looks like this:

Identify logical constraints

Specify an equation that satisfies these constraints

Consider the range parameters might take

Before seeing any data, use the mean as a “best guess”

After working through these steps, we can then (and only then) fit a corresponding statistical model to see how well our model fits the data. With this in mind, let’s work through how Shugart and Taagepera (2017) model the number of seat winning parties,

Readers in the US and the UK might assume that any district level elections must involve a set of parties fighting over a single seat. Indeed, in the UK it is even common to hear people refer to constituencies as seats. However, in most other contexts, this is not the case and, in PR systems, parties will compete in a single district over many seats instead. By convention, we call the number of seats that some district elects the “district magnitude” and denote it

Shugart and Taagepera (2017) note that the district magnitude,

Bringing Parties In

The model that Shugart and Taagepera (2017) derive is beautiful in its simplicity. What’s more, it does an extremely good job of predicting the number of seat winners in any given district, despite not using a single piece of data. It is, I think, a testament to just how far we can get by thinking about the systems that produce electoral data.

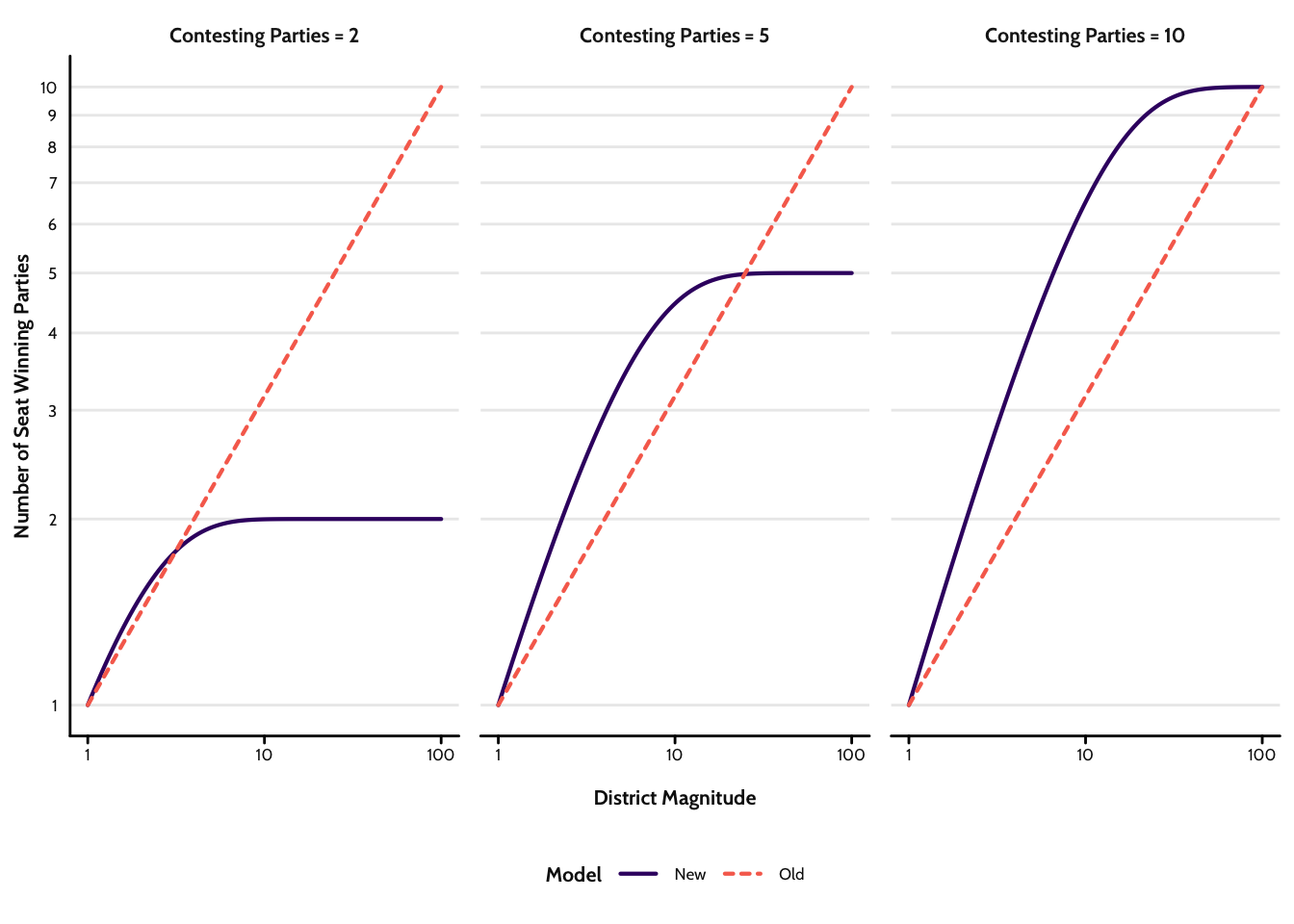

But, though the model is elegant and effective, it does have one limitation in a specific scenario. Recall that Shugart and Taagepera (2017) argue that the largest number of parties that a district might elect is

This might not seem like a significant issue, especially given that the existing model makes good predictions with such a simple formula. However, even well-designed models can face edge cases and, as Taagepera himself says, “Predictive models must not violate logic even under extreme conditions” (2008, 41). In this case, however, the model above makes 223 predictions that cannot occur given the real-world constraints imposed on cases in the CLEA data that I discuss above. Again, this might seem a trivial number but, as Popper argues, it only takes one black swan to falsify a theory. 223, thus, suggests an opportunity to refine the model further.

The Occupancy Problem

Another way to model the number of seat winning parties in some district would be to multiply the number of parties that contest the district,

Although the derivation is simple enough, I’ll make things easier to follow by breaking it into chunks:

As we lack any data, we do not know each party’s popularity. So, our prior expectations must be flat: as far as we know, each party has exactly the same chance of winning any given seat. This then implies that the probability that any given party will win any given seat is

A nice trick when faced with a problem like this is to recognise that at least one success is the same as not all failures. Since we know that the probability of one success is

Finally, since this equation tells us the probability of not winning a seat

Thus, the probability that any given party will gain at least one seat,

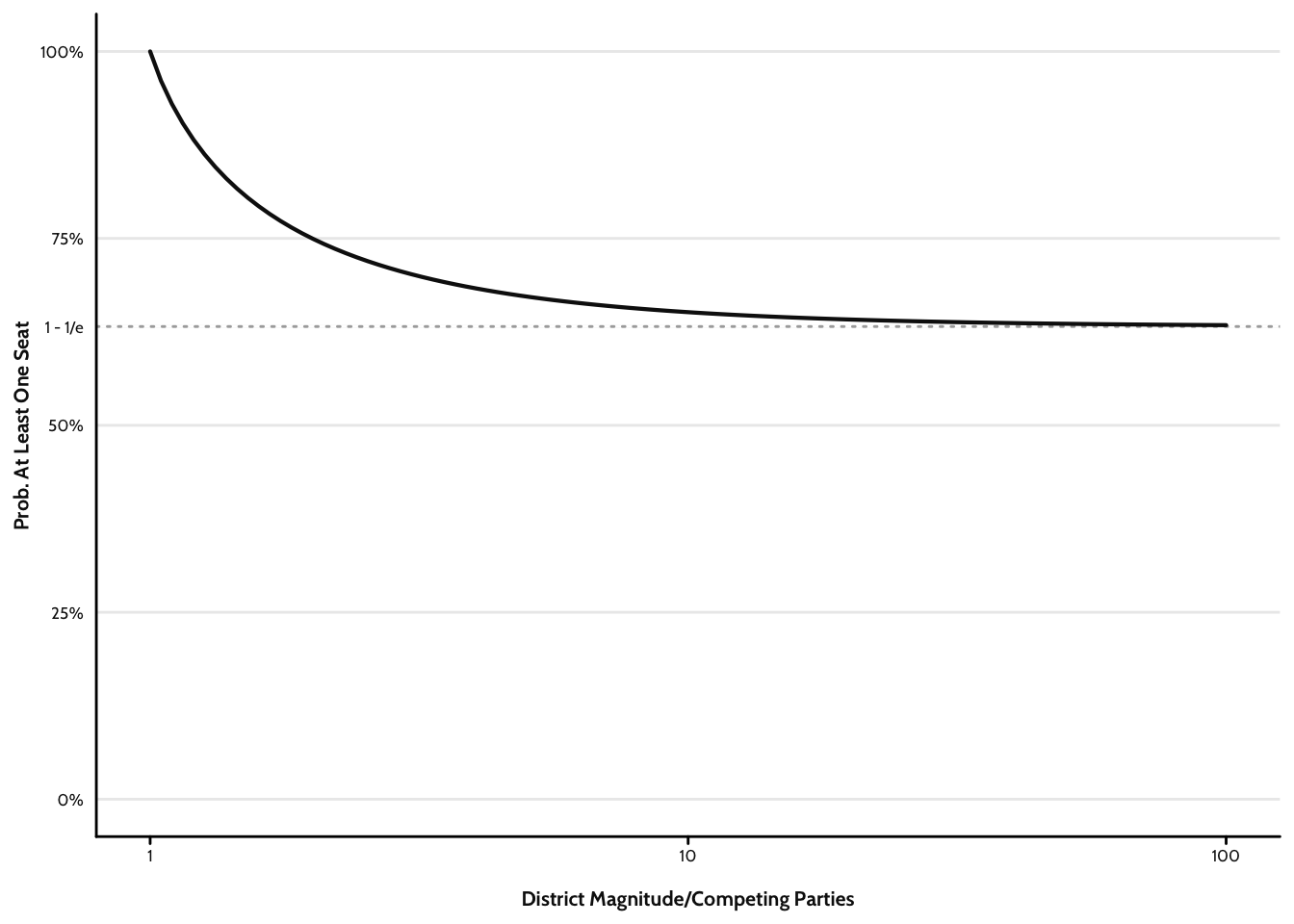

One nice thing about this equation is that as

To complete the model, all we need to do is to multiply this probability by

Figure 2 plots predictions from this function as the district magnitude,

Final Steps

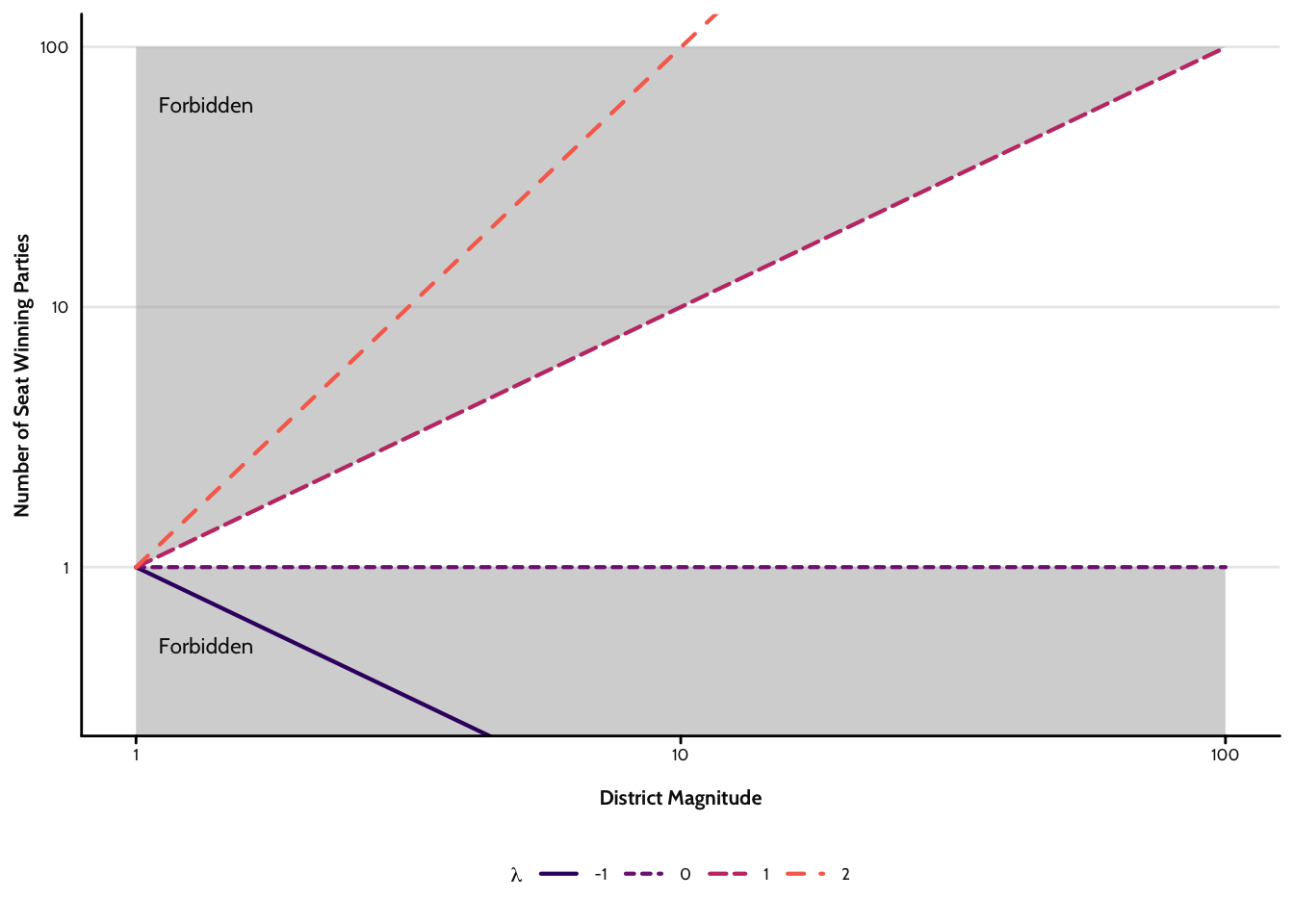

So far, the model makes predictions but lacks any parameters. This is a problem since we cannot either fit it to data or adjust the function’s slope. So we need some way to do this that still respect the known bounds that we set out above. The simplest way is to take

To complete our logical model, we need only determine the most likely value that

Since we know

The really nice thing about this is that, in the limiting case where